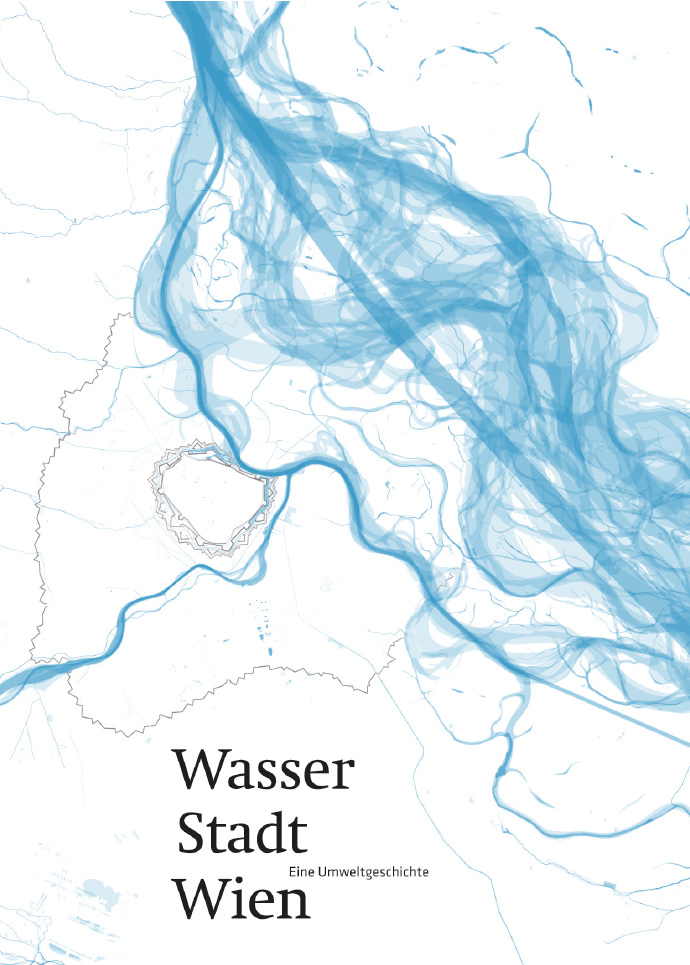

Danube Watch 2/2020 - Vienna and its Waters: an Environmental History

Vienna and its Waters: an Environmental History

T ourists visiting Vienna are often disappointed to discover that the historical centre of Vienna is located on a small canal, but by no means on the much sung-of "Schöne blaue Donau" (“Beautiful blue Danube”). In the present, even Viennese residents can hardly understand that Vienna is a water city. However, a look at the history of urban waters shows that this could once have been rightly asserted.

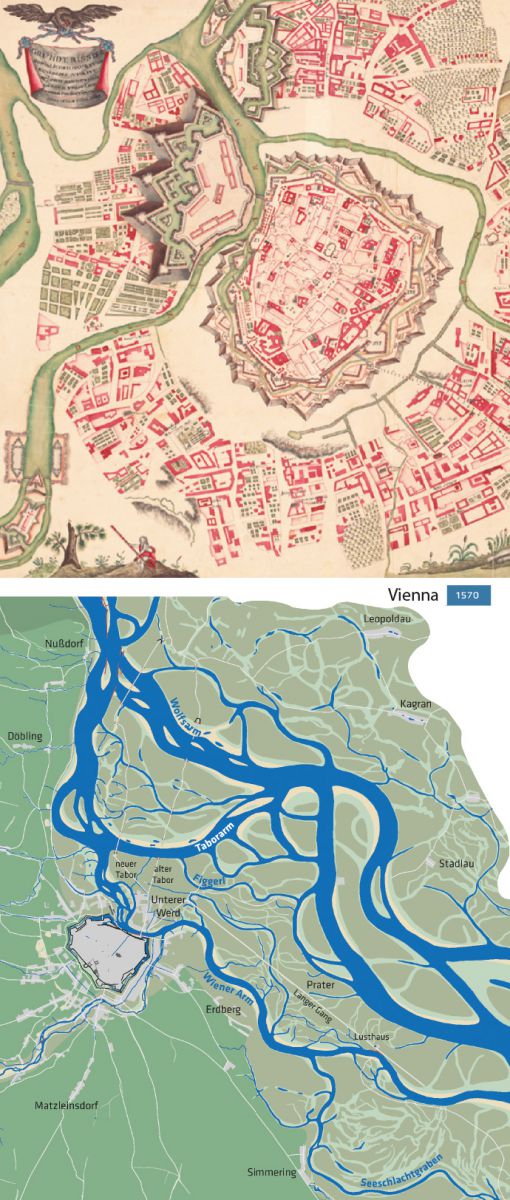

Before the First Viennese Danube Regulation in the years 1870 - 1875, the Danube branched into several arms in the Vienna Basin. The Danube landscape, with its dynamic river arms, few oxbow lakes and alluvial zones, reached a width of several kilometres. Both the Roman Vindobona and the medieval city were built on the banks of former large river arms, which might have been even the main arms during the respective time periods. Actually, Vienna was once located on the Danube. From the 13th century onwards, the main arm of the river shifted further and further to the north-east away from the centre. Countless water engineering projects followed. Until well into the 19th century, the supply of the city depended on a navigable Danube arm near the city. The "Wiener Arm", which had been called the "Donaukanal" (“Danube channel”) after 1704, therefore served primarily as a transport route. Along the banks, one could find the ship's landing places, storage yards for wood, markets or many administrative institutions that were entrusted with shipping and trade.

However, the Danube was by far not the only watercourse of the city. On the slopes of “Wienerwald” (“Vienna Woods”), numerous brooks sprang up, which flowed into the Danube. They determined the location of the suburbs and businesses, as well as the course of streets. The two largest streams were the Wien River and the Liesing. The mean discharge of the smaller streams did not even reach 100 litres/second, with the exception of the Alsbach. The Wien River, as a watercourse close to the city, was accordingly a centre of historical water usage in Vienna. A large part of the 110 mills that existed around 1825 within today's city boundaries were located here. They were built on mill streams that ran parallel to the Wien River. Here they could not be destroyed by the floods that occurred during heavy rainfall in a very short time. In addition, during periods of low flow, the water was concentrated in these small canals, whereas in the wide bed of Wien River, a large part of the discharge would have seeped away. At the other Wienerwald streams near the city, only a few mills were operated and these had to be stopped frequently because the water flow was too low.

From the 16th century onwards, the water quantity of these small streams decreased even further: as the population of the city grew, the number of drinking water wells increased. Springs also supplied the first water pipes - although until the 18th century, it was mainly the nobility and the imperial court that profited from this. All of these facilities and installations drew groundwater and reduced the already insufficient outflow. With a growing population, the discharge of sewage into the Wienerwald streams and the Danube channel also increased. From 1753 onwards, the city authorities promoted sewers to solve the disposal problem. It is remarkable that this intensified the pollution of Vienna's waters until around 1900. Before sewers existed, houses had cesspools, the contents of which were discharged into the Danube outside the built-up area. After, domestic sewage was discharged into the creeks and then into the Danube channel. In the 19th century, the Wienerwald streams and Danube channel increasingly degenerated into cloaks. According to historical sources, around 1870 the storage of fish in the Danube channel before sale had finally become a health risk.

The successive transformation of the Wienerwald streams into sewers finally sealed their fate. When the first cholera epidemic hit Vienna in 1831, main sewer canals were built on both banks of the Wien River. Generous plans to vault the river were realised only in small sections. This was different for the numerous other urban Danube tributaries. They gradually disappeared underground from the 1840s onwards. Only the upper reaches situated outside the built-up area remained, and today represent important aquatic habitats.

At present, a large part of the historic water city Vienna is hidden underground and only indirectly visible. For example, some streets in the 9th and 2nd districts follow former river arms of the Danube. In the suburbs, main traffic axes indicate the course of the former streams, as in the case of Alserbachstraße or Hernalser Hauptstraße.

The Danube, the Wien or the Liesing rivers as still existing urban surface waters experienced numerous technical interventions until the 1990s. Today, flood protection dams characterise all three waters. On the Wien and Liesing rivers, long stretches of the riverbed was also paved over. The Danube was continuously expanded for shipping and a decade-old hydroelectric power project was implemented in the 1990s. It is only in the last two decades that the restoration of the waters has come to the forefront.

The traces of Vienna's water landscape, the interlinkage of water and spatial development of the city as well as the beneficial uses and threats of urban waters, are the subject of a book on the environmental history of Vienna's waters, which was published in 2019.