Danube Watch 1/2021 - Biodiversity: “At The Collapse”

Biodiversity: “At The Collapse”

Two Vienna professors electro-fishing in the Danube: Herwig Waidbacher (left) and Friedrich Schiemer (right).

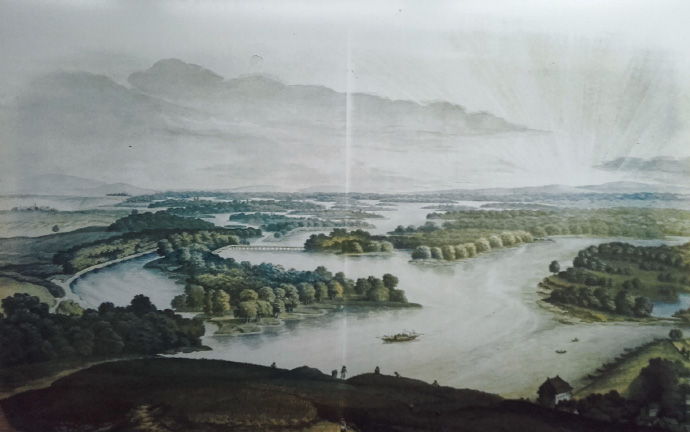

In days gone by, fish stocks were once to be found in incredible masses in our waterbodies. Freshwater fish were a hugely important part of people’s nutrient intake. In his unpublished studies, E. Weber recorded catches in the Danube from the city of Vienna to the town of Hainburg in Austria. Until the last quarter of the 19th century, 166 tons of fish were caught on average annually along that stretch. This was no overexploitation – though of course, the stream looked absolutely different than it does today. In those days, our Danube consisted of hundreds of Islands, plus many smaller and bigger sidearms. All the well-known anthropogenic pressures eventually changed our water-world completely.

Our fish stocks were affected massively too. Notable scientists have estimated a biomass-loss of our fish stocks of about 90% already before 1950. Where previously millions of fish had once thrived, by the middle of the 20th century only tens of thousands remained. But destruction of the environment went on. The Living Planet Index by the Zoological Society of London showed how from 1970 to 2012 – a mere 43 years – 81% of all vertebrates in freshwater died off, and vertebrates in freshwater means mainly fish.

Austria lies in the middle of Europe. In our country, the distribution range for the species of both West- and East-Europe meet. Therefore, we’ve got more than 70 species of fish in the Danube, along with 74 species of fish and 3 species of lampreys in its tributaries – far more than in any other river system in Europe. In any case, we find ourselves in the Danube, in a very fortunate situation, with only one species having gone extinct. The European sturgeon (Acipenser sturio). But don’t forget, that’s only just at the moment. All fish species in the Danube are endangered. Most of them are heavily endangered.

Painting by Friedrich Brand “Danube at Vienna about 1870”, currently on display at Dresdnerstraße U-bahn station in the city.

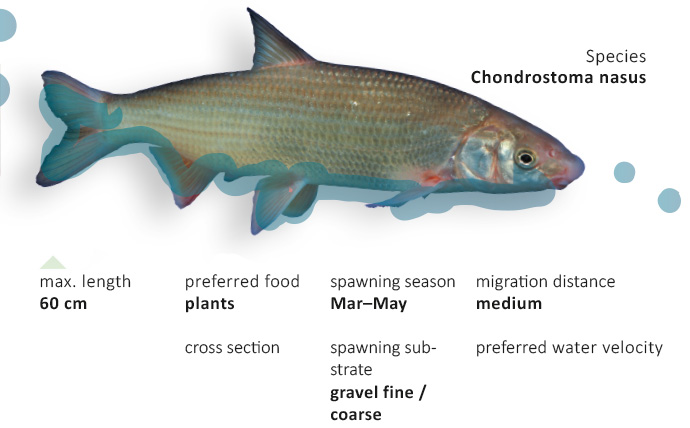

In around 1980, the scientists Fritz Schiemer and Hubert Keckeis at the University of Vienna began their famous investigations on spawning-behaviour of riverine fish in the Danube, east of Vienna near the town of Fischamend. Today the stretch comprises the Nationalpark Danube-Wetlands, and every single fish has been tagged. At the start, tens of thousands were registered. Nase (Chondrostoma nasus) comprised about 50% of the biomass, just as it had in the old days. However, year by year the stocks became lower and lower. In the years 2003 and 2004, only 3,000 Nase could be counted. By 2011, not a single Nase was detected at the generations-old spawning places. Within 3 decades the Nase had gone from mass-fish to an extremely endangered species. Especially noteworthy, in the Nationalpark, where everybody thinks the world should still be in closer to its natural order.

Today, we can see the same in the recently published results of the Joint Danube Survey 4. Biomass of Nase is at the present about 2% in the Danube; a fish, which had once amounted to the quantity of all other Danubian fish species combined. Nase was the “bread-fish” for commercial fishery and now it’s in danger of extinction. Alas, this goes for all of our fish species.

Destruction of environment and hand in hand destruction of biodiversity is happening right before our eyes, and it’s high time to notice it. Styrian magazine Natur & Land wrote in its 2/2021 edition that “84% of Styrian fishes are endangered”. The same goes for every other federal state in Austria. To protect biodiversity is now an important target in the EU. It’s imperative to find ways to protect our environment beneath the water’s surface, and achieving the aims of the Water Framework Directive and protecting biodiversity have to be seen as interdependent tasks.