Danube Watch 3/2017 - Urban wastewater treatment within European water policy

Urban wastewater treatment within European water policy

By the 1980s, pollution of our waters – rivers, lakes, coastal waters and groundwater – had become an inescapable fact, threatening not only the ecology of our water environment, but also human health and economic development including not only urban and rural development, but tourism as well.

Against this background, requests for action at a European level did not only come from the expert community, but also increasingly at a political level. June 1988 saw a Ministerial Seminar in Frankfurt bring together the then 12 Member States to

demand urgent legislative action addressing threats to Europe’s water resources, in particular on wastewater discharges and agricultural pollution. In the same year, a European Summit of Heads of States and Governments in Hanover supported these

objectives at the highest level.

The political priority of combating water pollution was further underpinned by the relatively swift adoption process by the European legislator: the Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive (UWWTD) entered

into force only 18 months after presentation of the legislative proposal.

Main elements of the Directive

Main elements of the Directive

The Directive provides for

- wastewater collection and treatment for all but the smallest ‘agglomerations’ (settlement areas and areas of economic activity of more than 2,000 population equivalents)

- numerical emission control values for wastewater treatment, basically ‘secondary’ (i.e. biological) treatment as a minimum requirement, plus additional nutrient removal in the catchment of so-called ‘sensitive areas’, i.e. areas with eutrophication problems

- permit procedures and pre-treatment for industrial wastewater

- monitoring of performance of wastewater treatment plants, and regular reporting; staged deadlines for achieving the environmental objectives in 1998, 2000 and 2005 respectively, depending on the size of the agglomeration and the characteristics of the affected waters. For the new Member States, which joined the EU in 2004, 2007 and 2013, transition periods are part of the Accession Treaties.

With further development and expansion of EU water policy through the Water Framework Directive (WFD), the UWWTD has been integrated into the management framework of the WFD to include river basin management plans and programs of measures, as has the Nitrates Directive.

Implementation experiences

Looking back over more than 25 years of implementation experience, several elements can be considered to be distinctly important. This is true for the adequate delineation of agglomerations, and

a careful assessment of various options, from centralised and semi-centralised systems to individual and alternative systems. Construction and operationtenance costs need to be duly assessed, as does the impact on affected waters (‘good

status’ to be achievedtained). As for individual and alternative systems within agglomerations, the indispensable precondition of ‘achieving the same level of environmental protection’ is required to shape considerations.

Operation

and maintenance of wastewater infrastructure has proven to be as important as planning and construction. This can be seen on a large scale in Malta where almost 100% of the population is connected to sewerage systems, and treatment plants are

in place. However, facilities are not performing properly because 100% of the wastewater discharged is not in compliance with the Directive, not least due to an excess of farm manure being discharged into sewers.

The November 2017 “International

Workshop on Wastewater Management in the Danube River Basin” provided further experiences.

Read more on page:

International Workshop on Wastewater Management in the Danube River Basin

Benefits – environmental and economic

Concerns about water quality rank amongst the top environmental concerns for European citizens, with

50% of citizens in all 28 EU Member States stating that they are worried about water pollution.

Whilst detailed economic studies on the benefits of good water quality are scarce, figures available show considerable benefits, both in

terms of percentage of GDP and of investments vs. economic benefits. A 1993 study for the island of Rhodes in Greece concluded that preventing degradation of bathing water quality would deliver benefits of 3% to the GDP. Along similar lines,

a 1997 study by the Agence de l’Eau Artois-Picardie for the Côte d’Opale in France concluded that benefits of € 300-500 million could be achieved in return for € 150 of investment in wastewater infrastructure. A study on people’s ‘willingness

to pay’ for better bathing water quality in a coastal area of the United Kingdom concluded that people were willing to pay an average 25-45 EUR per year for reduced health risks linked to bathing.

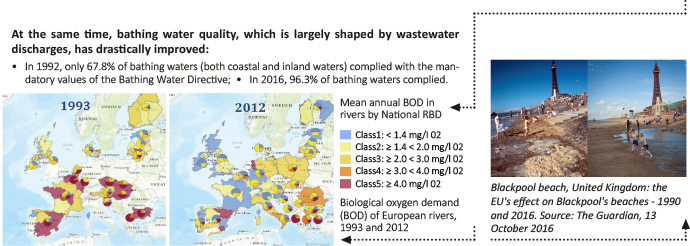

The past 25 years of implementation

of the UWWTD have delivered a distinct reduction of river pollution, as can be seen in the European Environment Agency comparative maps for 1993 and 2012.

Challenges ahead: some thoughts

Looking at the UWWTD from today’s understanding and from experiences gained, the following thoughts are expressed:

Treatment objectives are also, from today’s point of view, up

to date. To recall, the UWWTD has been complemented by the ‘combined approach’ established in the WFD. Where a quality objective or quality standard established under EU environmental legislation requires stricter conditions than those set under

emission control legislation, such as the UWWTD, the Industrial Emissions (IPPC) Directive or the Nitrates Directive, more stringent emission controls have to be set and implemented accordingly.

Monitoring and reporting requirements

seem – compared to more recent legislation such as the WFD, the Floods Directive or the Bathing Water Directive – to a certain extent vague. However, for a considerable number of years cooperation and joint action by Commission and Member States

has achieved solid wastewater reporting based on the principles of WISE (Water Information System for Europe) and contributed to increasing quality and user-friendliness of implementation reports. Looking at the reporting intervals, coordinating

these should be seriously considered, as current intervals show quite some degree of ‘diversity’:

- every two years under the UWWTD;

- every four years under the Nitrates Directive and under the Industrial Emissions (IPPC) Directive;

- every three and six years respectively under the WFD.

Public participation and involvement of citizens and stakeholders does not feature at all in the UWWTD, and transboundary cooperation only to a limited extent. However, it could be argued that all relevant measures linked to this Directive are

integrated into the framework of the WFD and thus covered within the transboundary cooperation and public information and participation provisions therein.

At the level of local, regional, national and European budgets, the challenge

of the future will be, to a considerable extent, the rehabilitation of aging sewerage systems, in parallel to and beyond the completion of sewerage systems and treatment plants. These sewerage systems date back across Europe partly to the late

19th, early 20th century. Given the considerable amount of financial resources required for such rehabilitation measures, the necessary financial planning will have to take place at all relevant levels.

All involved, decision makers

at local, regional, national and European level, experts and stakeholders will continue to face these challenges, for the benefit of our citizens and our waters.

The author: Helmut Bloech is former Head of the Water Sector of the Directorate General Environment of the European Commission. In this position, he was responsible

for development and implementation of EU water policy and legislation, including the Water Framework Directive and other directives on wastewater treatment, drinking water, bathing water and flood risk management. Between 2000 and 2010 he was

Head of Delegation of the European Union at the ICPDR.

The author: Helmut Bloech is former Head of the Water Sector of the Directorate General Environment of the European Commission. In this position, he was responsible

for development and implementation of EU water policy and legislation, including the Water Framework Directive and other directives on wastewater treatment, drinking water, bathing water and flood risk management. Between 2000 and 2010 he was

Head of Delegation of the European Union at the ICPDR.