Danube Watch 3/2017 - Identifying alternative financing for the water sector

Identifying alternative

financing for the

water sector

We are surrounded by the benefits of past investments, and the human cost of poor water quality is clear, from reduced economic productivity to childhood stunting due to endemic diseases. Yet mobilising the financing needed to secure water supply and build resilience to climate change is not as easy as it sounds.

Countries bordering the Danube River have benefited substantially from investments from the European Union since initiating the accession process, most of which have been in the form of grants. In these countries, public funding from taxes and external transfers can represent a sizeable share of total sector investment, up to 60% in countries such as Montenegro, Albania or Kosovo. EU funding rose steadily between 2000 and 2015, and accounts for about 60% of total international transfers to the region, yet much remains to be done to meet EU Directives, particularly in the area of wastewater collection and treatment. It will therefore be a major challenge to provide finance in a tough environment where major funding is needed to tackle the refugee crisis and adaption to climate change.

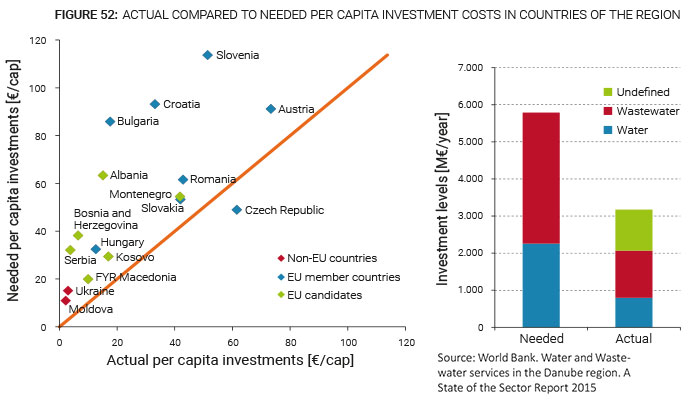

The World Bank is looking into what it will take to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for the water sector and beyond. At a global level, for drinking water and sanitation services alone, we have estimated that at least US $114 billion will be needed annually to meet universal access to safely managed water and sanitation in 140 low and middle-income countries, 60% of which will be needed for sanitation. Investment requirements vary substantially from region to region: for the Danube countries alone, the 2015 State of Sector report released by the Danube Water Program estimates that “total water and wastewater investments in the region are around €3.5 billion a year. This is significantly lower than the €5.5 billion estimated to be needed by the region’s governments to achieve EU or national targets”, pointing to a significant gap in financing. This €2 billion gap in water infrastructure investments means that new sources of finance will need to be found every year if sector targets are to be achieved at current levels of ambition.

A good example of this can be seen in Croatia, where the municipality of Rijeka managed to tap into local domestic sources to finance a swimming pool complex by issuing a ten-year bond. The project was deemed to have both social and tourist value and its financing stimulated considerable interest in the local population, including a number of local personalities. This investment has been a stepping-stone for Rijeka to revitalize its beachfront and take on the mantle of European cultural capital in 2020.

Since the State of the Sector report was released in May 2015, very few countries in the region have taken sufficient steps to identify new sources of finance for the water sector, preferring to rely on what seems to be a relatively steady flow of official development finance in the form of grants or development bank loans. This is an unsustainable strategy however. Official development finance (ODF) will not be sufficient to address the water sector financing challenge. Although ODF for the water sector has been steadily increasing, it has remained relatively modest with US $14 billion per year being channeled into ODF to the water sector worldwide. Scarce public funds will need to be leveraged much further and used wisely in future.

Using commercial finance

A particularly attractive opportunity lies in the potential for mobilising domestic commercial finance for water. This is an untapped source of finance, which can also provide a profitable investment opportunity for local investors. Commercial finance can take many forms, ranging from microfinance for household investments, supporting local entrepreneurs and domestic bank loans – all the way to issuing bonds on domestic capital markets. Many water sector operators in both the European Union and the United States finance their investment programs through tapping into private sources of finance. Many such operators, especially in the United States, are publicly-owned.

The Danube Water Program is a partnership programme funded by the Austrian Ministry of Finance and implemented by the International Association of Water Supply Companies in the Danube River Catchment Area (IAWD) and the World Bank.

At first sight, commercial finance may seem more expensive than development financing, which is generally provided free of charge, or at favorable concessional rates. But ODF alone is insufficient to meet the needs of water sector financing in the Danube region and commercial financing can offer many advantages that counteract the higher financing costs over time. In countries with high currency risk and significant inflation, borrowing in domestic currency eliminates foreign exchange risks. It also allows tapping into pools of domestic financial resources that have so far been largely ignored, such as pension funds, institutional or social impact investors, when the latter may be looking for low-risk, low financial return investments with high social benefits. In addition, using commercial finance could help public utilities to introduce robust commercial principles in their operation and management.

Governments at both national and local levels need to develop a realistic vision of what it takes to achieve their own goals, in line with EU obligations and SDGs, and in particular to define which targets can be achieved within which timeframes.

So what prevents other cities, or countries, in the region from adopting a similar approach in the water sector? To attract commercial finance, public utilities need to establish themselves as creditworthy, with transparent and sound corporate governance structures and with viable financial performance to recover most, if not all, of their capital and operating costs. At the same time, commercial lenders need to be encouraged to “test the waters” of lending to a non-familiar and potentially political sector.

With this objective in mind, the government of Albania recently conducted a Strategic Financial Planning exercise, with financial support from the European Union and technical assistance from the World Bank. This helped the government define a realistic “Water for the People” financing plan, with carefully balanced tariff increases and more modest targets than originally envisaged. Furthermore, mobilising commercial finance for service providers that are credit-worthy will allow governments to use scarce public funds in “needier” areas of the sector, such as rural sanitation, where prospects of credit-worthiness are more distant.

This is not a “business-as-usual” approach and will likely face initial resistance on the part of sector stakeholders.

International financial institutions such as the World Bank can play a key role in facilitating such a transition by supporting strategic financial planning exercises in the region and blending our financial resources with domestic commercial finance resources. This involves, for example, providing technical assistance and capacity building, and co-financing investment packages while putting in place first-loss agreements and providing guarantees. We see this as part of our new role to facilitate and “de-risk” investments so that all countries can have a fair chance of meeting their own ambitious targets under the global SDG umbrella. Such an approach to financing the sector will need to be applied to all types of water sector investments, including establishing adequate systems and investing in infrastructure for water security, and ensuring that all water users - farmers, industry or energy producers - use water wisely.

The World Bank acknowledges the role of ICPDR as a successful example of regional, transboundary collaboration in the field of water resources management, with a mission closely aligned with that of the World Bank in achieving a water secure world for all.