Danube Watch 1/2018 - Sustaining the Danube Across Climate Frontiers

Sustaining the Danube Across

Climate Frontiers

“That water doesn’t actually come from a canal. It comes from a river. And that river is altering rapidly, because of climate impacts. Five years ago, you had a massive drought that affected more than 30 million farmers. When the next, worse drought comes and the farmers want their water, will you still be able to generate energy? Are you prepared to make some hard choices during a crisis? And do you know how to avoid a crisis?” He leaned back: “Now I know why you are here.”

In the past decade, climate change has shifted from an environmental concern to a fundamental economic and development security issue. How do we ensure that assets and infrastructure will perform under novel climate conditions? Can our cities, farms, healthcare, environmental, and energy systems cope with extreme events? Do national and local plans for development make sense given the range of futures we may be facing? Are we prepared — or preparing — for the range of difficult choices that lie ahead?

Climate change is not equally relevant or important to all decisions and issues. However, as the energy minister came to understand, sometimes climate change is critical, or even severely critical. Sorting out when climate change is relevant, how it might be relevant, and how to respond are the decisions we must prepare for today as water professionals.

The Challenge of Water Resilience

AGWA (the Alliance for Global Water Adaptation) was founded in 2010 in Sweden by a small group of water professionals from governments, development banks, professional societies, think tanks, NGOs, and businesses.

It was co-chaired by an economist with the World Bank and a policy specialist from the Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI) and led by a freshwater scientist. Our network includes almost 1200 water professionals worldwide. Collectively, we see evidence that shifts in the water cycle are already here, but climate science has little confidence to offer in terms of predictions about the speed, form, and intensity of future impacts when we need a strong quantitative framework, such as in engineering, economics, planning, and finance. We can also see that some types of projects, especially infrastructure and ecosystems, are highly exposed to climate impacts. In both cases, long lifetimes and low tolerance for failure mean that climate change is usually a very important consideration — both for existing and new projects.

Flexibility as an adaptation strategy refers to maintaining options as conditions evolve and to prevent being trapped in a strategy that may be difficult to reverse

Should we respond by ignoring uncertain impacts, add a larger safety margin, average a mix of climate projections, or embrace the range of uncertainties for the future and prepare for a wider range of possibilities?

At AGWA, we see the state of the art in resilient water management shifting away from approaches that optimize a single climate future (sometimes called top-down exposed) towards methods that emphasize robustness and/or flexibility, which are more generally called bottom-up risk assessment.

Fostering Resilience from the Bottom Up

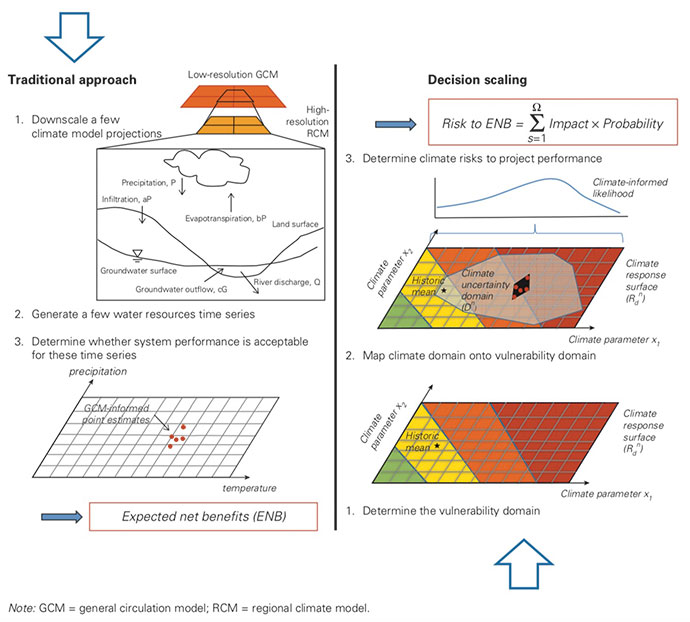

In general, bottom-up methods share the assumption that we should assess risk by looking at the inherent “breaking points” of the system or project in question. For agriculture, that breaking point may be a level of yield produced per hectare. For a utility, the number of households served without failure per unit of time. Performance below this point is considered unacceptable. A model is then generated that can test when climate-relevant conditions might violate that breaking point and how credible these conditions might be, such as a wetter or dryer future. Robustness and flexibility define the two strategies for responding to credible climate futures. Robustness means planning for a broad spectrum of possible futures; not just a wetter or dryer future but, for instance, both a wetter and a dryer future. Beginning around 2009, a methodology called decision scaling was developed to implement robust solutions. Casey Brown at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, has been instrumental in innovating and applying decision scaling to cities, utilities, transboundary water bodies, energy systems, and planning processes. With support from the World Bank, in 2015 he and Patrick Ray (University of Cincinnati) created a stepwise support system for applying decision scaling to a wide range of water projects for loan officers (Ray & Brown 2015).

Decision scaling

Comparison of decision scaling with top-down approaches to assessing climate risk. Credit: Ray, Patrick A.; Brown, Casey M. 2015. Confronting Climate Uncertainty in Water Resources Planning and Project Design: The Decision Tree Framework. Washington, DC: World Bank. ©World Bank.

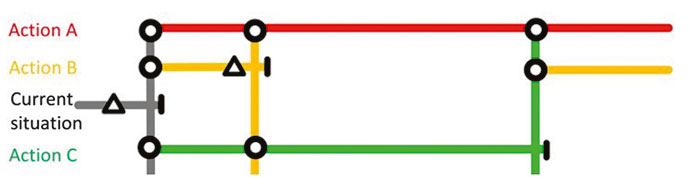

Adaptation pathways is essentially a formal methodology for implementing flexible solutions in the face of complexity and uncertainty. The figures shows a comparison of alternative decision making and action pathways (horizontal lines), with decision "tipping points" that act as triggering points in time to transfer stations between decision pathways; potential movement between pathways is shown through vertical lines. Tipping points reflect reaching a level of certainty that the chosen pathway needs to be re-considered, such as from changes in flood frequency. Some pathways such as Action B may not have function in all conditions, requiring a transfer between pathways. Credit: Marjolijn Haasnoot and Deltares

A specific methodology called adaptation pathways developed by Marjolijn Haasnoot at Deltares in the Netherlands has been widely applied to situations where complexity, cost, and uncertainty make selection of a single strategy challenging and risky.

As with decision scaling, adaptation pathways emphasize the need for clear performance indicators. Both approaches lend themselves to practical engagement with diverse stakeholders, including the identification of ecological variables such as fisheries, endangered species, or water quality as “virtual” stakeholders. A variety of new applications of these methodologies have recently been published, or will soon be available, including a UNESCO publication oriented towards water managers called Collaboration Risk Informed Decision Analysis (CRIDA), which offers decision support for hydropower and water utilities and the application of new resilience criteria for green and grey water infrastructure financed through the climate and green bonds market. A Resilient Danube Basin?

A Resilient Danube Basin?

Despite being new concepts, these methods are being explored regionally in the Dniester River by the UNECE, the US Army Corps of Engineers, and the governments of Ukraine and Moldova to target flood control.

These methods offer several opportunities to the Danube region: basin-scale risk and opportunity assessment, national scale sectoral prioritization, and application to individual water projects. Given the dense interconnections across political and institutional boundaries, the need for a shared and operational vision of resilience is essential for ensuring a sustainable Danube in the 21st century.